A Man, a Plan, a Canal: Panama

17.01.2019 – Shelter Bay Marina, Panama

Usually, night-time is when things are most interesting in tropical rainforests, but in Shelter Bay Marina I found the first exception to this rule. Although the forest was heavily degraded, howler monkeys, keel-billed toucans, turkey vultures and more could be seen during a short morning walk. I expected a similar level of activity and diversity at night, but I was in for a surprise. Switching my head torch on revealed what I first assumed to be dewdrops in the grass. Upon closer inspection, they turned out to be a dizzying number of small wandering spiders. I also encountered a few drab frogs and the odd gecko on my night walks, but nothing else of note.

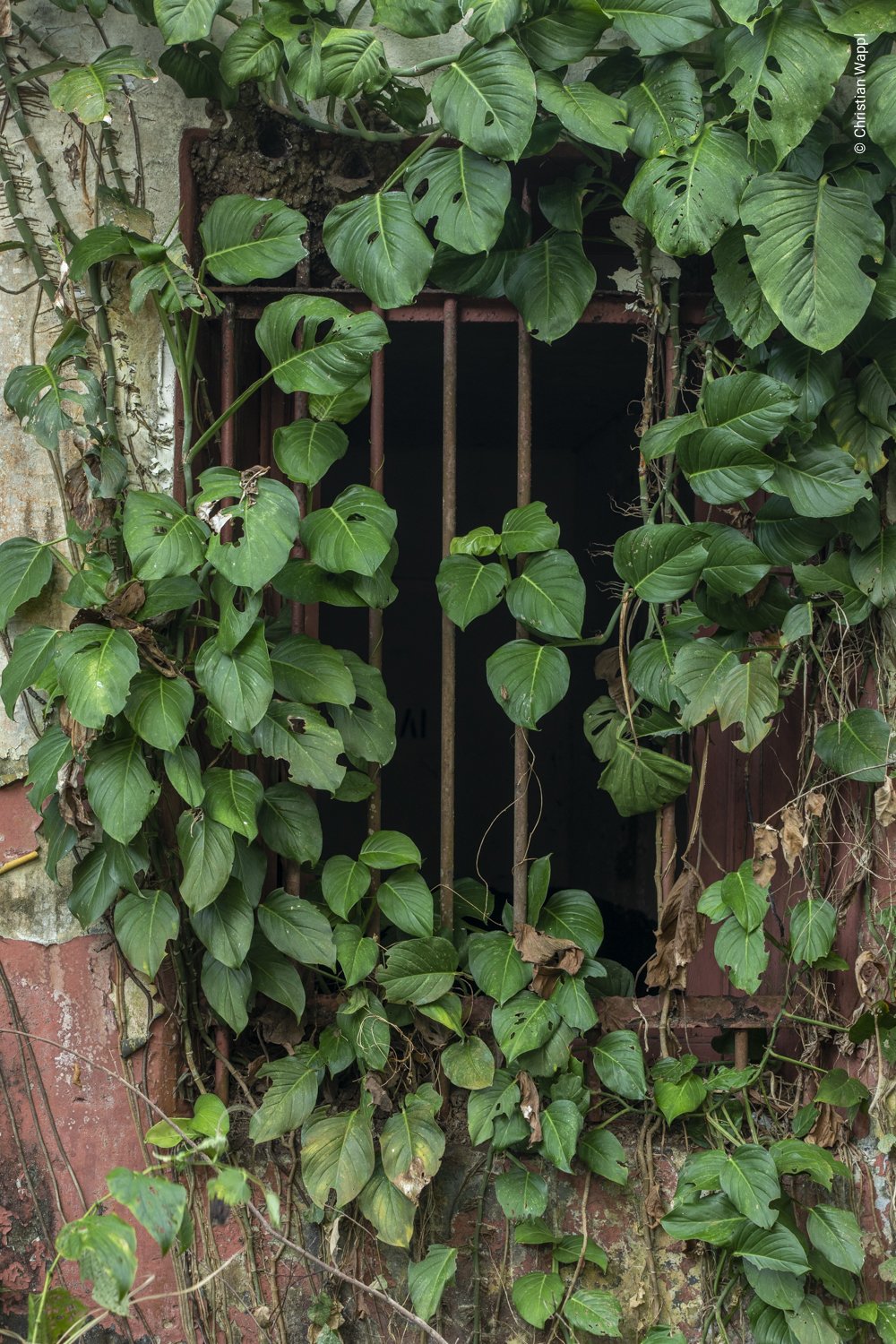

Luckily, there was plenty to see despite the less than pristine condition of the rainforest. The US army had been stationed at Shelter Bay Marina until the late 90s and their presence continues to be felt in the surrounding areas. The outer coastline near Shelter Bay is fortified with several naval gun batteries, which are slowly being consumed by the jungle. Inside the gun batteries, all manner of wildlife had made themselves comfortable. I encountered bats, whip spiders, land crabs, frogs and, of course, large cockroaches. The latter taught me quickly where not to put down my backpack. I came back to find a couple of cockroaches scurrying around on it, the largest of which was as long as my index finger. One had managed to weasel its way inside, so I spent a good fifteen minutes scouring my backpack to ensure there were no other ones in there.

Further inland from the gun batteries, a compound of barracks can be found. One such military barracks would consist of a living room, a kitchen, a small room for air-conditioning unit and a toilet downstairs. Upstairs there would be three bedrooms, a bath and four cupboards. Unlike the gun batteries, the jungle was somewhat kept at bay from the barracks. The lawn and shrubs seemed to be maintained regularly, and there were traces of a recent coconut harvest. Inside the barracks, there were all manner of dead, mummified creatures - mainly birds and bats, but also a snake, a frog and a large tarantula. At first, I assumed they’d just gotten trapped inside and perished, but the large number made me suspect that maybe, the buildings had been fumigated at some point in the last years. I did encounter a handful of live creatures inside the barracks - a few bats, a couple of stingless bee nests, and a gecko or two. A colony of chestnut-headed oropendolas - crow-sized birds - had built their characteristic hanging nests in the palm trees between the barracks, and a turkey vulture surveyed me inquisitively from a lamp post. But compared to the gun batteries and storage facilities, there was little animal presence in and around the barracks.

Female yellow-headed gecko - only males have the species’ defining trait

For a week, I spent almost every waking minute exploring these abandoned facilities. Without a doubt this was my favourite part of the trip. But my stay here was rapidly coming to an end, since our time slot for the Panama Canal was approaching fast. To traverse the canal, each yacht needs a total of at least six people: four deck hands (for fastening up to four ropes at the same time), the guide (to guarantee a smooth process), and the captain (for obvious purposes). The guide was provided by the authorities of the canal, but we were still two people short. Luckily, we managed to find two volunteers just in time. The brothers Nick and Peter Ryley had a substantial amount of nautical experience – Nick even was a competitive sailor. Peter was a biologist with some interesting tales about travelling the tropics and filming wildlife. We really couldn’t have found a better pair of deck hands. We left late in the afternoon after several delays. I was happy about the delays, because I had some unfinished business back at the ruins. I’d already given up on the yellow-headed gecko but managed to get the desired shot at the last second.

We left Shelter Bay Marina in the late afternoon and welcomed our guide, Eduardo, shortly afterwards. The whole canal endeavour was to be strictly a motorized affair – i.e., no sails. By the time we reached the first lock, it had gotten dark. A spectacular sight, nonetheless, and truly a marvel of human engineering. Although the pollution from the larger ships crossing the canal is surely immense, land-based fauna and flora profits from the canal. The surrounding forest is strictly protected, as any kind of logging activity could lead to erosion of the canal’s shores. We rendezvoused with two other yachts and tethered the Imagine to them side-by-side, before entering the lock and going upwards. After passing two locks, we cast off the Imagine from the two other sailing yachts and lashed onto a buoy to spend the night in Gatun Lake. This massive artificial lake was the world’s largest at the time it was created around a hundred years ago.

The next day, we set out to cross the remainder of the canal with our new guide, Manuel. Motoring along through in the sunny weather was a pleasant experience, enhanced by the surprisingly good state of nature along the banks of the canal. Peter and I passed the time looking for birds. Around noon, we took a short break and tethered to a buoy because we were ahead of time. I’d been itching to take a dip in the canal, and here was my chance. Lake Gatun is home to American crocodiles, but Manuel assured me that this part of the canal was crocodile-free. Nevertheless, crocodiles are known to occasionally stray a good distance from their usual home range. I didn’t want to tempt fate and didn’t linger in the turbid waters for too long. We resumed our journey and soon afterwards, we reached the locks. The way up had been interesting, but only when going down it was possible to truly appreciate the height gap bridged by the locks. By the time we passed underneath the Bridge of the Americas into the Pacific Ocean, the sun was setting. Our guide was picked up bis his colleagues, and we also said goodbye to Nick and Peter, whom we dropped off in a nearby marina.

Day 2 of traversing the Panama Canal

My final days in Panama were spent anchoring off Panama City. In the morning after the passage of the canal, the depth gauge of the Imagine began displaying odd values. At first, we suspected a shallow, but the numbers kept dropping. At one point, we were supposedly anchoring in 1.7m of water - fairly unlikely considering the Imagine’s draught of 2.1m. At that point we were convinced it was a technical error, but the true reason became apparent when hundreds of seabirds arrived. Countless tiny fish had formed a swarm so dense the depth gauge interpreted it as solid ground. I took a few shots of the spectacle, but for the most part decided to take a break from photography for a change and enjoy the moment before I went back to the chilly weather of Europe. Laying back in the cockpit of the Imagine and watching pelicans, frigatebirds and cormorants hunt - as a final day in Panama, I could’ve done a lot worse.

In my experience, even the slightest effort at speaking their language is greeted with enthusiasm in Spanish-speaking countries. My taxi driver to the airport was no exception and proved to be delighted at my conversation attempts in broken Spanish. First, he told me all about his own sex life (“Sure I’m married and have two kids, but you know how it goes. A man just needs a lil’ extra from time to time!”), then he wanted to know the important things about my country (“Do women shave down there in Austria?”). Finally, he even offered to take me to his favourite brothel. I politely declined but appreciated the intent behind the gesture.

While I had an uneventful flight home, my parents were already getting ready to sail to French Polynesia – another multi-week-journey, comparable in length to the crossing of the Atlantic. They would stay in Polynesia for the rest of the year, until I came to re-join them in late autumn.